“Chúng ta là những gì chúng ta liên tục làm. Sự xuất sắc không phải là một hành động mà là một thói quen.”

Được cho là Aristotle vì câu trích dẫn này có thể là, ý tưởng rằng tính nhất quán là rất quan trọng để thành công được khẳng định rõ ràng bởi các vận động viên, ông trùm kinh doanh hàng đầu thế giới và Tiến sĩ Kristaps Jurjāns của Bệnh viện Đại học Lâm sàng Pauls Stradins ở Riga, Latvia.

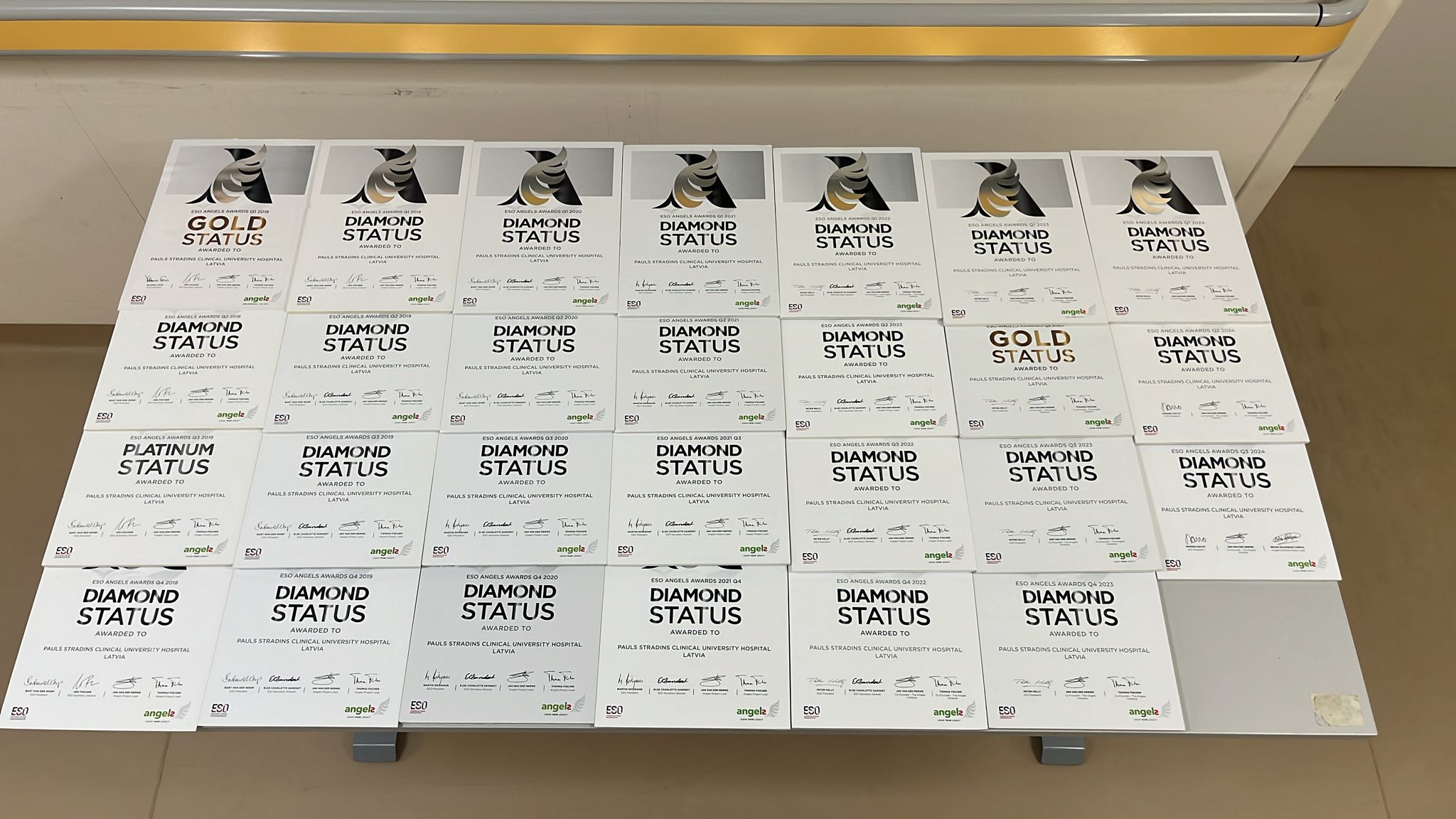

Nếu có bảng xếp hạng cho Giải thưởng Angels, bệnh viện của Tiến sĩ Jurjāns sẽ đứng đầu, với 24 giải thưởng kim cương và không có kết thúc. Họ lần đầu tiên giơ tay vào đầu năm 2018 khi họ đăng ký với Angels, và đến cuối năm đó bắt đầu có một chuỗi giải thưởng kim cương nóng mà đáng lẽ sẽ không bị gián đoạn nhưng vì thời hạn nhập dữ liệu bị lỡ vào mùa hè năm 2023.

“Bạn bắt đầu một cái gì đó, làm việc với nó cho đến khi bạn nghĩ rằng nó hoạt động và sau đó bạn tiếp tục làm nó”, Tiến sĩ Jurjāns giải thích. Một khi quý vị đã đạt được tính nhất quán, điều trị đột quỵ cấp tính trở thành "một thói quen" và nếu đó là một thói quen hạng nhất thì "một người dân năm thứ hai có thể đưa ra quyết định điều trị chính xác trong khoảng 10 phút".

Tiến sĩ Jurjāns cho rằng sự tự tin của ông là do bác sĩ đột quỵ nổi tiếng nhất ở Latvia đào tạo và người chiến thắng Giải thưởng Tinh thần Xuất sắc ESO năm 2020, Giáo sư Evija Miglane. Nhưng dưới sự lãnh đạo của ông, đội đột quỵ tại Pauls Stradins đã đến sân khấu quốc tế và ở lại đó. Trong một sự kiện của Angels Train-the-trainer, nơi ông được mời làm diễn giả, Tiến sĩ Jurjāns đã tham gia với khán giả để trình bày về can thiệp sau cấp tính, Dự án Arrow và thấy một cơ hội khác để cải thiện.

Được phát triển bởi ba y tá tạiBệnh viện Đại học Khu vực Málaga ở Tây Ban Nha, Dự án Arrow chuẩn hóa việc chăm sóc đột đột quỵ cấp thông qua một hệ thống mũi tên được mã hóa bằng màu giúp các bác sĩ, y tá và thậm chí cả người khuân vác dễ dàng xác định loại đột quỵ và bên bị ảnh hưởng, và thông qua chi tiết truy cập mã QR của các phác đồ điều trị cho mỗi ngày, chẳng hạn như kiểm tra thường xuyên chứng Chứng rối loạn nuốt, đường huyết và sốt.

Bác sĩ Jurjāns đã bị ấn tượng bởi sự đơn giản và rõ ràng do việc sử dụng màu sắc và biểu tượng bao gồm cả những biểu tượng cho biết liệu một bệnh nhân đã được kiểm tra khó nuốt hay chưa và, sau khi được kiểm tra, những hạn chế nào đối với lượng thức ăn của họ. Trong vòng vài tháng, một phiên bản thích ứng của dự án đã bắt nguồn từ đơn vị đột quỵ của chính ông.

Đây là điều có thể giúp

Nuốt thịt người là một công việc phức tạp. Phải mất khoảng 50 cặp cơ và một số dây thần kinh sọ để thức ăn được vận chuyển một cách an toàn từ thìa đến dạ dày – một hành trình bao gồm ba giai đoạn.

Trong giai đoạn miệng, lưỡi của bạn thu thập thức ăn, sau đó làm việc với hàm để di chuyển nó xung quanh miệng của bạn sẵn sàng để nhai. Nhai phân hủy thức ăn theo kích thước và kết cấu phù hợp, được hỗ trợ bởi nước bọt làm mềm thức ăn.

Trong giai đoạn hầu họng, lưỡi đẩy thức ăn vào phía sau miệng, kích hoạt phản ứng nuốt đi qua thức ăn qua cổ họng. Để ngăn thức ăn hoặc chất lỏng xâm nhập vào đường thở và phổi, hộp thoại đóng chặt và ngừng thở. Nói chuyện giữ cho đường thở mở, đó có thể là lý do tại sao mẹ bạn nói với bạn không nói chuyện trong khi bạn đang ăn.

Giai đoạn thực quản chỉ kéo dài khoảng ba giây, trong đó thức ăn hoặc chất lỏng đi vào thực quản và được đưa vào dạ dày.

Đó là một tương tác cơ bắp được phối hợp tốt mà hầu hết mọi người không bao giờ nghĩ đến ngoại trừ những trường hợp khi thứ gì đó họ đang ăn hoặc uống “đi sai hướng”. Sau đó, một chiếc gag

hoặc phản xạ ho thường sẽ cố gắng giải quyết vấn đề.

Tuy nhiên, nếu đột quỵ hoặc rối loạn hệ thần kinh khác cản trở phản ứng nuốt, các miếng thức ăn có thể chặn đường đi của không khí và thức ăn hoặc chất lỏng ở trong đường thở có thể xâm nhập vào phổi, dẫn đến viêm phổi do hít phải.

Bác sĩJurjāns gặp khó khăn do tỷ lệ hít phải cao trong đơn vị đột quỵ của ông, ảnh hưởng đến 30% bệnh nhân. Đây là điều có thể hữu ích. Anh ấy đã dịch các tài liệu sang tiếng Latvia và giới thiệu chúng tại bệnh viện vào tháng 8, làm việc với một chuyên gia dinh dưỡng và chuyên gia trị liệu ngôn ngữ để cung cấp thêm chất cho các hướng dẫn của Dự án Arrow.

Còn quá sớm để đo lường tác động của tỷ lệ hít phải, nhưng có những mặt trái rõ ràng, bao gồm thực tế là các y tá hiện được trao quyền để đánh giá khả năng của bệnh nhân và họ, cùng với các chuyên gia dinh dưỡng, có thể theo một số con đường nhất định để đưa ra quyết định về chế độ ăn của bệnh nhân thay vì chỉ dựa vào kinh nghiệm thực tế của họ.

Các biểu tượng không chỉ hữu ích cho nhân viên y tế; chúng còn giúp người thân hiểu được những hạn chế về dinh dưỡng của bệnh nhân, Tiến sĩ Jurjāns nói.

Một vấn đề mà anh ấy vẫn đang cố gắng giải quyết là sự thay đổi về kết cấu đã thay đổi (được phân loại là mật hoa, mật ong và bánh pudding) khiến thực phẩm an toàn để nuốt cho bệnh nhân tùy thuộc vào điểm Chứng rối loạn nuốt của họ. Ở đây, tính nhất quán cũng sẽ là chìa khóa thành công.

‘Hãy chắc chắn rằng anh ấy không trở nên tồi tệ hơn’

Lần gặp gỡ đầu tiên của bác sĩ Jurjāns với một bệnh nhân đột quỵ là lễ rửa tội chữa cháy vào ngày đầu tiên hoặc thứ hai sau khi ông cư trú tại khoa thần kinh. Ông nhớ lại rằng bác sĩ, đã bắt đầu Tiêu huyết khối, đã được gọi đi và để lại cho ông phụ trách hướng dẫn quan sát bệnh nhân và ghi chú mỗi mười lăm phút. Cô ấy để lại cho anh ấy một bức ảnh chia tay đáng sợ: “Cô ấy nói hãy đảm bảo không có gì trở nên tồi tệ hơn.”

Đó là một khoảnh khắc lo lắng đối với một nhà thần kinh học thực sự muốn trở thành một nhà chỉnh hình. Khi chương trình đó đã đầy, anh đã làm mẹ mình ngạc nhiên khi theo bước chân của bà vào khoa thần kinh. Họ có cùng họ và khi một bệnh nhân gần đây hỏi liệu cô có liên quan đến “bác sĩ Jurjāns nổi tiếng” hay không, bác sĩ Jurjāns đầu tiên không hoàn toàn hài lòng. (Cô ấy chắc chắn cũng rất tự hào.)

Ông trở thành một chuyên gia về đột quỵ vì lý do tương tự như ông muốn chỉnh hình - ông muốn làm bẩn tay và trong thần kinh học, đột quỵ là nơi hành động.

Tiến sĩ Jurjāns nói: “Luôn có điều gì đó để khắc phục”. Ngay cả khi bạn phải giữ một số phần thưởng của mình trong các hộp vì tường hiển thị trở nên quá nhỏ. “Nó xuất hiện trong sóng đối với tôi. Cảm hứng đến rồi tôi tạo ra sự thay đổi, tạo ra điều gì đó mới mẻ.”

Một số thay đổi trong số này có thể không đáng kể – như một biểu tượng trên bìa kẹp hoặc sách hướng dẫn Angels Stroke Care at Home được dịch sang tiếng Latvia để ngăn ngừa hít phải sau khi xuất viện – nhưng chúng thực hiện công việc quan trọng là cứu sống nhiều người.

Trong phòng đột quỵ tại Bệnh viện Đại học Khu vực Málaga, nơi có một bản tóm tắt để chuẩn hóa chăm sóc điều dưỡng được phát triển thành Dự án Arrow, tính nhất quán cũng đang mang lại thành công. Họ đã lọt vào bảng giải thưởng vào cuối năm 2023 và vừa giành được giải thưởng kim cương thứ hai liên tiếp.

Thật hợp lý khi tin rằng, về bất kỳ bệnh viện nào giành được những viên kim cương liên tiếp, họ đã biến sự xuất sắc thành một thói quen. Tính nhất quán rất quan trọng. Và nếu bạn tiếp tục làm điều đó đủ lâu, cuối cùng bạn sẽ cần một bức tường lớn hơn.